The revolutionary scope of the movements of 1968 was epochal not only for the repercussions it had on the political equilibrium and social dynamics but also for the theoretical and formal upheavals in the field of architecture.

To disrupt the architectural vocabulary in the tense climate of those years was the Dutch architect Herman Hertzberger, who in 1968 was commissioned to design the offices of the new headquarters of an insurance company in the city of Apeldoorn: the Central Beheer Offices.

The anthropological structuralist approach with which Herman Hertzberger challenged the rigid modernist impositions provided an innovative vision of workspaces centered on users and their needs.

Structuralism[1], in fact, gives a user-centered interpretation of the architectural project and, as Herman Hertzberger himself states:

«always leads to the dialectics of the individual and the community. A structure provides cohesiveness, so that individual qualities, however subordinate to the whole, play more than a subordinate role and constitute an essential part of the whole, just as the separate fibers of a fabric not only assure cohesion but may also help to determine the natural of the whole. The principle of the reciprocal interdependence of the individual and the communal is at the very heart of structuralism.»

Herman Hertzberger

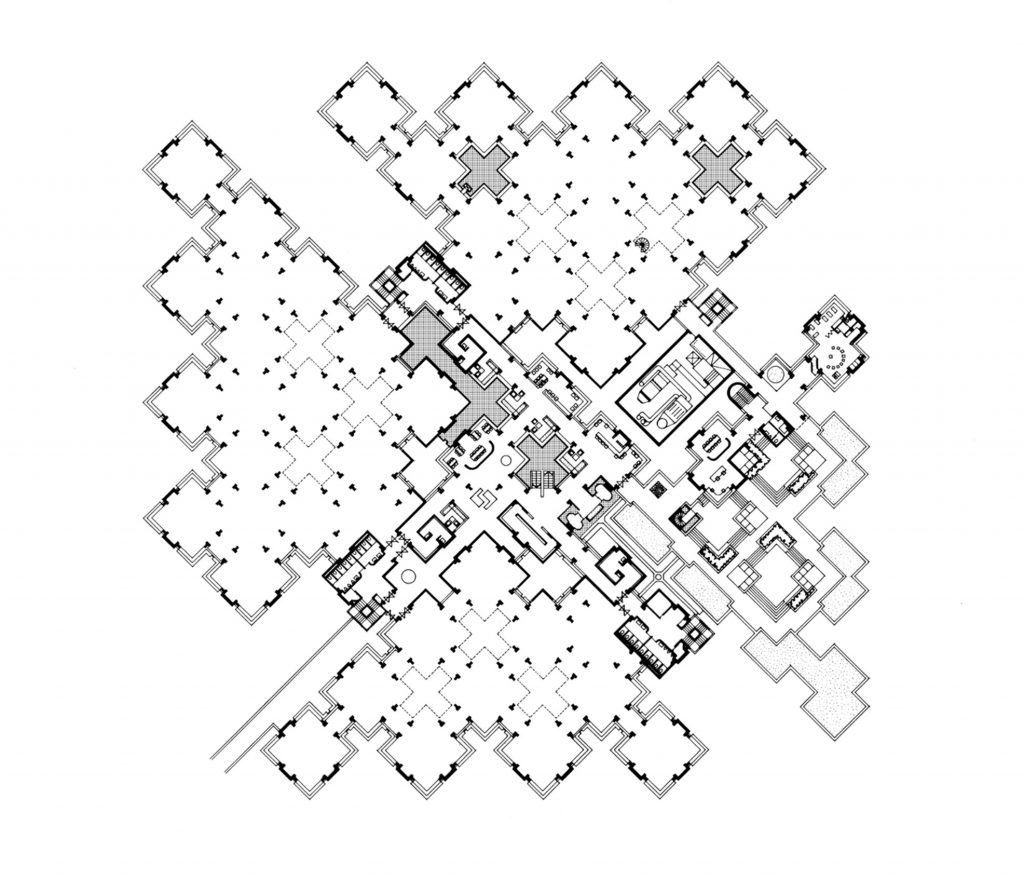

The demands of a less hierarchical and bogged down society were accompanied in that period by a strong reaction against the masters of the modern movement, which the Dutch architect managed to handle with elegance, choosing the path of dialogue over that of confrontation. To the rigid structure of rationalism he contrasted, in fact, the organic modularity of 56 blocks of various heights that at any time, as needed, could be increased.

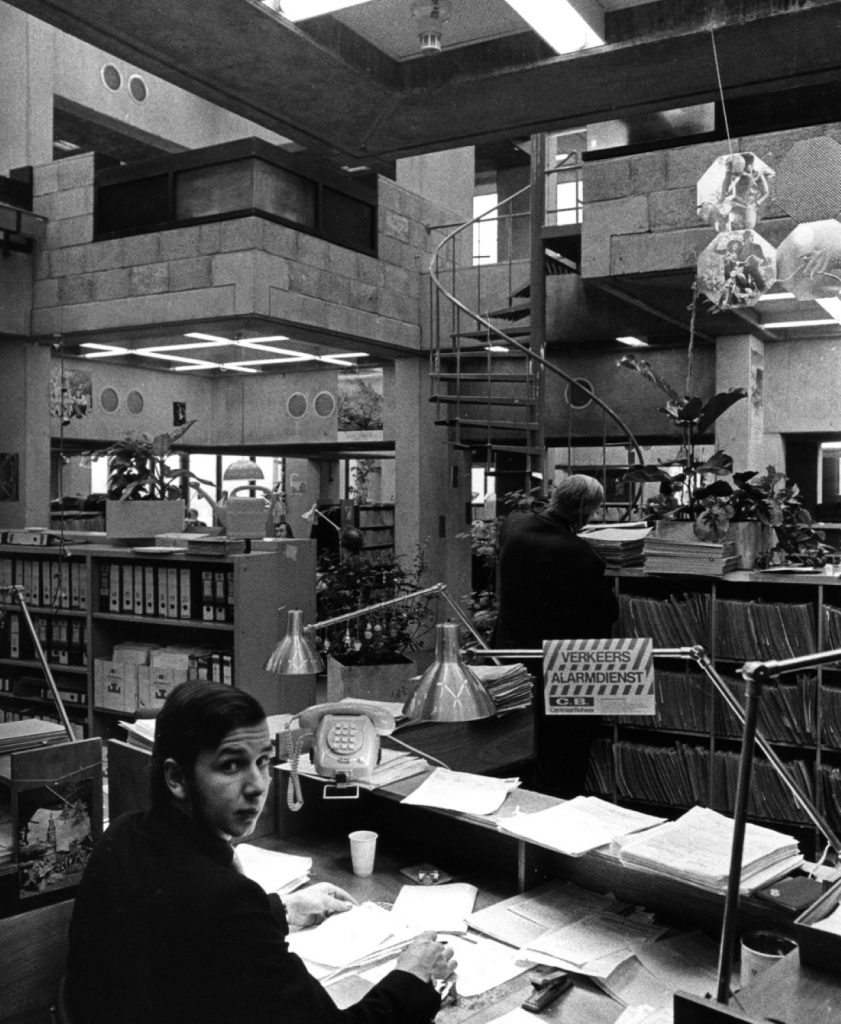

Instead of cold, glossy and perfectly balanced materials, he preferred the contrast between natural and artificial elements such as wood and metal, and the contrast between the smooth and transparent surfaces of glass and the opaque and rough surfaces of beton brut. To the rigidly functional space he preferred a more democratic and flexible mixitè.

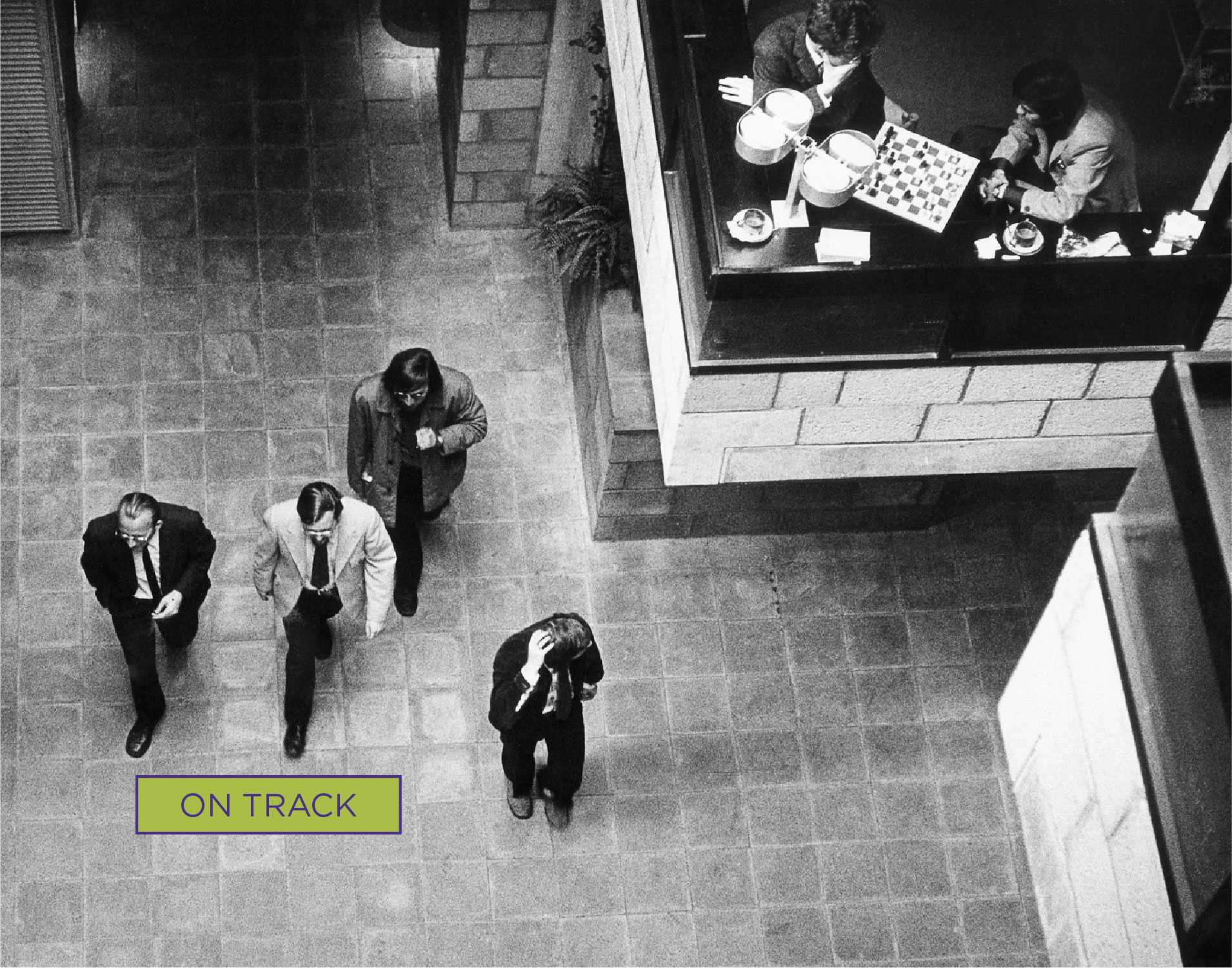

In response to an architecture enslaved to power, Hertzberger proposed an environment capable of improving the conditions of workers and promoting meetings and interactions. Well-being and social relations are the pillars on which the entire project is based.

The model that inspired Herman Hertzberger was the qasbah, the typical fortified Arab citadel that, by gathering its social spaces within a tangle of streets and terraces, gave the citizen the idea that the city was intimate and safe, and that everyone had the opportunity to meet with others and interact.

William Curtis describes the project this way:

«Herman Hertzberger’s design looked like a cashbah of narrow alleys, winding paths, and changing levels, but it was still based on a modular system. Where the high-tech view implied total control of image and finish by the designers and corporate administration, the rough concrete blocks, prefabricated beams, and irregular floors of the ‘workers’ village’ embodied an ideal of participation, leaving it up to the individual to complete the bare structure by the inclusion of knick-knacks, plants, and other objects that could create a sense of ownership of the place.»

CURTIS 2006, P. 596

Bibliography

Curtis 2006 – Wiliam R. Curtis, Moder Architecture since 1900, Phaidon Press Limited, London 2002.

Sitography (from which the images were taken)

https://www.ahh.nl/index.php/nl/

https://www.ahh.nl/index.php/en/projects2/12-utiliteitsbouw/85-centraal-beheer-offices-apeldoorn

https://juliaknz.de/post/649705677676232704/herman-hertzberger-central-beheer-1972-apeldoorn

https://melanieaolivera.files.wordpress.com/2018/01/olivera_module9_centraalbeheer.pdf

https://pure.tue.nl/ws/portalfiles/portal/96766652/Beerkens_0772331.pdf

[1] Theory and methodology affirmed in various sciences since the early twentieth century, based on the assumption that every object of study is a structure, that is, an organic whole and global whose elements do not have independent functional value but assume it in the oppositional and distinctive relationships of each element with respect to all others of the whole. (Treccani)