Workplaces as we conceive it today is an invention of the Industrial Revolution which, in order to minimize costs and maximize profits, concentrated the work spaces and marked the times at a fast pace.

The theory formulated by the American engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor (1856-1915) by mimicking the rigid hierarchical division and obsessive surveillance of the panoptic[1] prison-factory designed by the English economist Jeremy Bentham in 1791, accelerated this process of industrialization and continued to influence the design of work environments to the present day.

The alienation produced by the Taylorist assembly line, in the factory and in the offices, did not go unnoticed to the Finnish architect Hugo Alvar Henrik Aalto (1898-1976), who, invited immediately after the WWII to the United States as a visiting professor, had the possibility to think about the technological culture of that New World that had always fascinated him and to perceive

«its limits: excessive industrialization, standardization, dehumanization of production. Instead, he sees in the figure of Frank Ll. Wright a clear synthesis, an indication of a direction in which to move».

Prestinenza Puglisi 2019, p. 297

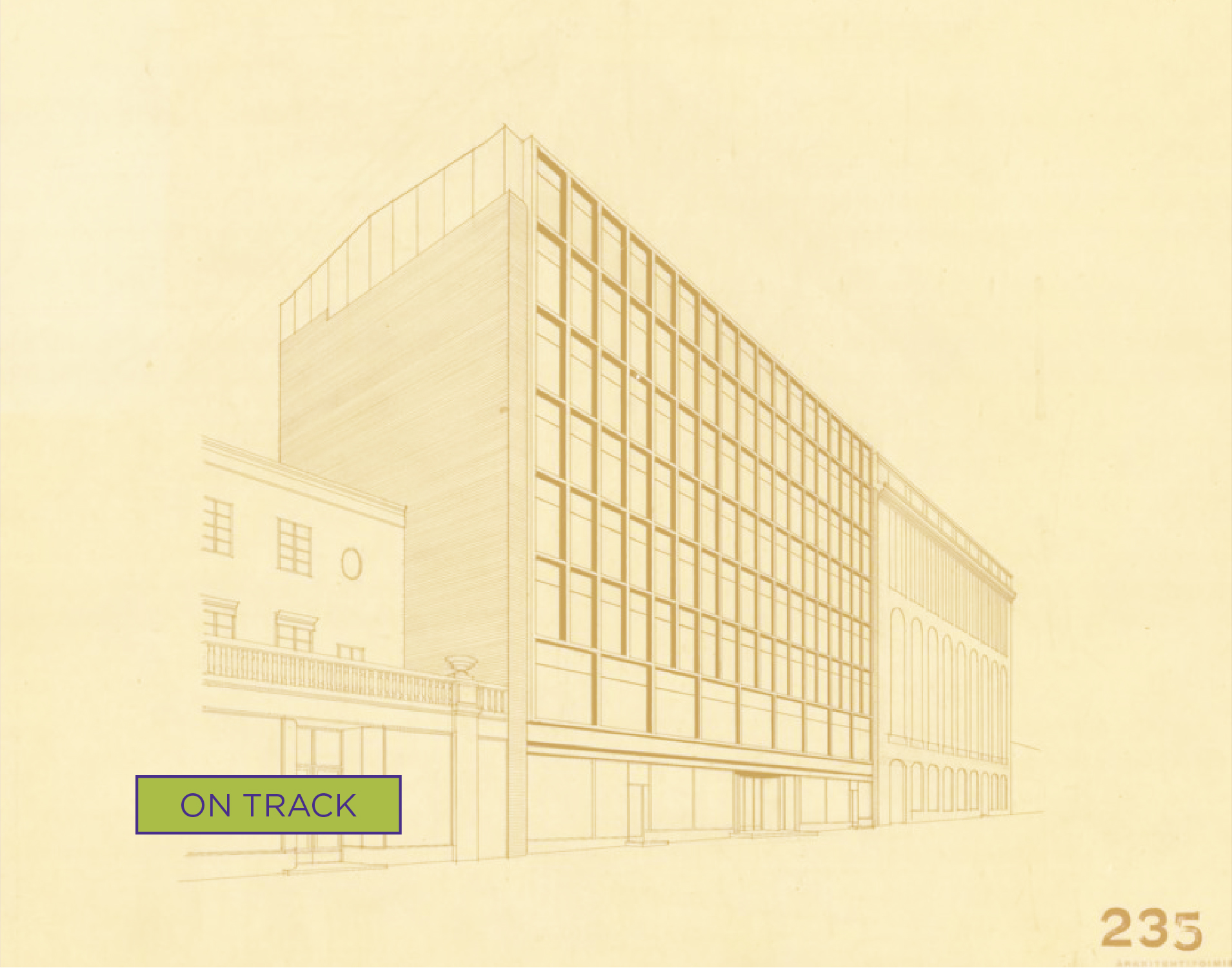

The opportunity to put the American experience into practice and develop his own idea of an office came to him in 1951, when he returned to Helsinki and won the competition launched by the owners of Hakasalmen Oy for the construction of a commercial building on a plot of land. of 1630 sqm.

The urban space with which Aalto had to confront offered an important challenge because it was made up of very different buildings, in terms of style and materials. These include Eliel Saarinen’s commercial building in red brick from the Classicist period and the Litonii Domus by Gustaf Leander and Valter Jung with which the Finnish architect set himself up in continuity. «Aalto opted for a structure that was connected with its neighbors through a harmonious compositional rhythm, but without any structural imitation. The neutral facade with its grid composition is also found in other commercial and office buildings designed by Aalto in the Helsinki city centre. The choice of metal as the main facade material came naturally because the client, Rautakauppojen Oy, was a ironmongery company».[2]

The innovation, however, is found inside, where the building is treated at the same time in its domestic (the name Rautatalo, in addition to referring to the names of the owners, Rautakonttori Oy and Rautakauppojen Oy, literally means “iron house “) and urban dimension. A large courtyard of white Carrara marble, known as the Marmoripiha, surrounded by travertine galleries, contrasts with the austere and dark facade, allowing light to filter through the 40 skylights on the ceiling[3]. A space that, as the author himself said, was built from the inside out, and which recalls a Michelangelo excavation capable of giving voice to the deepest spirit of the materials and which with its cafeteria for 120 people, its bubbling fountain and exclusive boutiques explicitly refer to the concept of an Italian square.

The Piazza, with its natural materials and the presence of nature and people, is the stratagem that Aalto uses to humanize spaces, giving them a strong social connotation. It is his personal way of overturning the Taylorist vision of the working environment as an intensive and alienating space, in favor of a bright, warm and welcoming environment, capable of reducing tensions and promoting social relations.

We must recognize Aalto, (as well as Frank Lloid Wright and Richard Neutra), the desire to lead architecture on a less “rational” and more humanizing ground, anticipating ideas that today still struggle to be recognized.

As the Finnish architect Juhani Pallasmaa argues:

«In the mid-thirties Alvar Aalto wrote about ‘Extended Rationalism’, urging architects to expand rational methods also to the psychological (Aalto uses the terms ‘neurophysiology’ and ‘psychophysiological field’) and mental areas. Both Wright’s and Aalto’s masterpieces are examples of an architecture that lovingly embraces us, something that could hardly be expressed intellectually. It is an architecture that connects directly to our human nature through the intuitive wisdom of the architect».

Pallasmaa 2021, p. 69

Bibliography

Curtis 2006 – Wiliam R. Curtis, Moder Architecture since 1900, Phaidon Press Limited, London 2002;

Foucault 1993 – Michel Foucault, Sorvegliare e punire. Nascita della prigione, Einaudi Editore, Torino 1993;

Pallasmaa 2021 – Juhani Pallasmaa, Sarah Robinson (edited by), Mind in architecture. Neuroscience, Embodiment, and the Future of Design, MIT Press, Massachusetts 2015;

Prestinenza Puglisi 2019 – Luigi Prestinenza Puglisi, La storia dell’architettura. 1905-2018, Luca Sossella Editore 2019;

Saggio 2010 – Antonino Saggio, Architettura e modernità. Dal Bauhaus alla rivoluzione informatica, Carocci Editore, Roma 2010.

Sitography

https://www.alvaraalto.fi/en/architecture/rautatalo-office-building/

https://en.docomomo.fi/projects/rautatalo-office-building/

[1] The Panoptikon is a detention facility designed to allow an overseer to look (opticon) in all (pan) directions. Foucault defines it thus: «Closed space, cut with precision, guarded at every point, in which individuals are inserted in a fixed place, in which the slightest movements are controlled and all the events recorded, in which an uninterrupted work of writing connects the center to the periphery, where power is exercised without interruption, according to a continuous hierarchical figure, in which each individual is constantly found, examined and distributed among the living, the sick, the dead – all that constitutes a compact model of disciplinary device» (Foucault 1993, p. 215).

[2] https://en.docomomo.fi/projects/rautatalo-office-building/

[3] The initial project involved a total emptying of the entire core of the building, from the first to the seventh floor, but was opposed by the owners for economic reasons and reduced to just two floors of galleries.